1. Introduction

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, many popular tourist destinations have been facing problems related to overtourism and are working on countermeasures. While travel used to focus on the satisfaction it brings to people and the economic benefits to local communities, now the impact of tourism on the environment and local society has become more important. In France, interest in environmental issues has increased after the pandemic, leading to a shift towards sustainable tourism. On April 13, 2023, the France Tourism Development Agency announced that, based on the government’s tourism plan (France Destination 2030), it had signed a partnership with the French Environment and Energy Management Agency to promote sustainable and responsible tourism. They plan to invest €70 million (about 94 billion KRW) from 2022 to 2024 in developing ecotourism, renovating mountain accommodations, and strengthening environmental criteria for hotel classifications. Additionally, Air France, the French national airline, aims to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 30% by 2030 through the use of sustainable fuels and eco-friendly catering. Furthermore, the France Tourism Board has developed various eco-friendly tourism products to promote sustainable tourism.

This case study aims to highlight the importance of soft power in culture and tourism by examining Paris’s eco-friendly plans and the symbolic significance of its landmarks, focusing on the Eiffel Tower, which attracts numerous tourists worldwide, and the Paris Summer Olympics.

2. Paris’s Carbon Neutrality and the Sustainability of the 2024 Summer Olympics

On December 12, 2015, at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change held in Paris, 196 parties came together to adopt the Paris Agreement. The Kyoto Protocol mandated binding emission reductions only for 37 developed countries with high greenhouse gas emissions. However, the Paris Agreement requires nearly all countries to participate in climate action by submitting their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) every five years, which are then reviewed to ensure implementation, with the expectation that each new NDC will represent a higher level of ambition than the previous one.

On November 4, 2016, to celebrate the Paris Agreement coming into force as international law, Paris lit up the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe with green lights. Every year, Paris attracts many tourists, and although the Eiffel Tower uses a lot of energy due to its dazzling presence visible from all over the city, Paris is currently transforming into an eco-friendly city. Cities consume more than two-thirds of the world’s energy and account for over 70% of carbon dioxide emissions. Over the coming decades, decisions regarding urban infrastructure such as construction, housing, energy efficiency, power generation, and transportation will have a tremendous impact on carbon emissions. Therefore, it is crucial to develop plans for carbon-neutral cities.

France is transforming its cities with a focus on Paris, the most visited city by tourists. Recently, Paris has installed wind turbines on the Eiffel Tower and is evolving into a sustainable city. Through these efforts, it aims to demonstrate sustainability as a tourist destination and Olympic host city to global citizens while reducing carbon emissions. Therefore, this case study intends to examine the sustainable transformation process of the Olympics and France’s landmark, the Eiffel Tower.

Sustainable City, Paris

Paris is making significant efforts to become an eco-friendly city. The city is involved in some of the world’s most dense and efficient public transportation systems, as well as in environmental protection, water resource management, biodiversity, and responsible production and consumption. To combat global warming, Paris has already reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% between 2004 and 2018, aiming for net zero by 2050. To adapt to climate change, Paris has created cool spaces during the summer—such as squares, gardens, museums, and libraries—where people can escape the heat. To prevent air and noise pollution and improve air quality, the city encourages walking and cycling. Furthermore, between 2014 and 2018, 15 hectares of urban agriculture and 15 hectares of parks and gardens were developed to promote biodiversity and provide ample green spaces for strolling. Paris also promotes responsible production, consumption, and a circular economy. In 2017, the city launched the “Fabriqué à Paris” (Made in Paris) label to promote locally produced goods and products crafted by Parisian artisans to the general public. This allows consumers to shop for artisan-made foods, furniture, decorative items, clothing, and fashion accessories produced within the city. In 2007, Paris adopted an active climate action plan. As a result, from 2004 to 2018, the city reduced its carbon emissions by 20% and greenhouse gas emissions by 25%. The third Paris Climate Plan (2018) accelerated carbon offsetting and sequestration initiatives from 2020 to 2030 through reducing energy consumption, developing renewable energy, adapting to climate change, and accelerating local transitions. Paris aims to reduce local carbon emissions by 100% by 2050 to achieve its zero-emission target and is working to engage local stakeholders in carbon offsetting to reduce emissions by 80% compared to 2004 levels to reach net zero.

Currently, Paris is implementing various policies to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. By 2030, solar panels are expected to be installed on 20% of Parisian rooftops. Already, 76,500 square meters of solar panels have been installed on roofs across the city. Additionally, to prepare for the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Paris is creating pedestrian zones, walking paths, and eco-friendly transportation to help both visitors and residents enjoy the city while making it more sustainable. By 2024, all diesel vehicles will be banned within the city, and by 2030, gasoline vehicles will also be prohibited. The city is also transforming to allow its 2 million residents to access all essential services—such as public transportation, shops, and schools—within a 15-minute walk from their homes.

2024 Paris Olympics

France is set to host the Summer Olympics in Paris for the first time in 100 years since the 1924 Games. The Paris 2024 Organizing Committee plans to cut carbon emissions in half compared to the averages of the 2012 London and 2016 Rio Olympics. This goal reflects both the IOC’s Olympic Agenda 2020+5 and the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Although there is currently no definitive solution to reduce carbon emissions from large-scale events, the 2024 Paris Olympics aims to set a global example for sustainable practices to reduce emissions. Moving forward, carbon reduction will become a binding requirement in all Olympic host city contracts. Starting in 2030, hosting agreements will include mandatory provisions to minimize both direct and indirect carbon emissions.

Paris 2024 is minimizing new construction in accordance with the IOC’s philosophy of a low-impact Olympics that adapts to the needs of the host city and its residents. Approximately 95% of the venues will be existing facilities (renovated and modernized as needed) or temporary structures. Olympic venues were selected to be accessible by public transportation. Paris 2024 is setting sustainable standards by promoting energy conservation, innovation, and creativity at this major sporting event. The Olympic and Paralympic Games will be powered entirely by renewable energy (clean electricity and biogas). All venues will be connected to the grid through the utility company Enedis and supplied with electricity generated from wind and solar power plants operated by EDF. Avoiding the use of diesel generators will reduce carbon emissions by 13,000 tons. The Olympic Committee aims to provide 13 million meals and snacks sustainably during the sports events. France targets carbon emissions of 1 kg per meal instead of the current average of 2.3 kg. Accordingly, 80% of ingredients will be sourced from France, with 30% of them being organic. The amount of plant-based products will be doubled, while single-use plastics will be reduced by half. The Eiffel Tower and Trocadéro projects, two landmarks of Paris, involve redesigning and transforming the entire area—from Trocadéro to Champ-de-Mars and École Militaire—into new green spaces prioritizing pedestrians and eco-friendly transportation. For the 30 million annual visitors to the Eiffel Tower, pedestrian-priority streets have been created to provide relaxing spaces for families to enjoy.

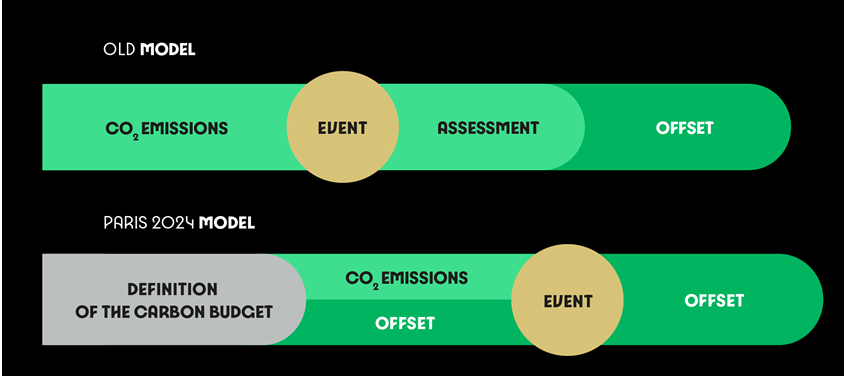

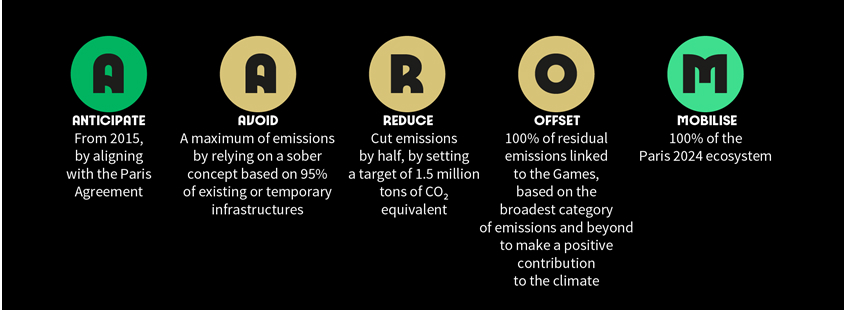

Paris 2024 applies the ARO approach (Avoid, Reduce, Offset) and has introduced two additional steps: Anticipate (A), which involves forecasting emissions and taking proactive measures, and Mobilise (M), which focuses on leveraging the appeal of the Olympics to drive action.

• Anticipate: Previous Summer Olympics emitted an average of 3.5 million tons of CO2. Paris 2024 considers this as a starting point and is developing tools to measure carbon emissions.

• Avoid: By using 95% existing or temporary facilities and constructing only venues that can be used after the Olympics in the surrounding areas, Paris 2024 reduces not only its impact on the climate but also the overall impact of the event.

• Reduce: Paris 2024 accurately identified emission sources and proposed solutions for all activities, including low-carbon structures, renewable energy, and sustainable catering. As a result, Paris 2024 set a target not to exceed 1.5 million tons of CO2, which is half the average carbon emissions of previous Summer Olympics.

• Offset: Paris 2024 considered Scope 3, the broadest category of emissions, which includes indirect impacts of the Olympics such as spectator transportation. Unavoidable carbon emissions will be offset through projects designed to provide both environmental and social benefits across five continents. By supporting the initiation and development of climate-friendly projects in France, Paris 2024 aims to become the first international sporting event to offset more carbon than it emits.

• Mobilise: Paris 2024 harnesses the potential of sport to unite everyone involved in the Olympics—including staff, partners, athletes, and citizens—through this process. To support this, Paris 2024 launched the “Climate Coach” app, designed to help staff become aware of and reduce their personal and professional carbon emissions.

After the 2024 Paris Olympics, 8,876 trees will be planted on the site of the Olympic and Paralympic Village in Seine-Saint-Denis. Parks and 6 hectares of green spaces will be created for pedestrians and eco-friendly mobility. Additionally, using bio-based materials, geothermal energy, solar panels, and architecture that promotes air circulation, the area will accommodate 6,000 residents and be transformed into an environmentally friendly experimental city for the future.

3. Paris’s landmark, the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower and Net Zero

Every year, millions of visitors come to Paris to see the Eiffel Tower. As one of the most iconic structures in the world, the Eiffel Tower is now transforming into an eco-friendly landmark. This demonstrates to people around the globe that even landmarks can evolve sustainably without losing their symbolic significance. By installing renewable energy systems on its structure, the Eiffel Tower shows the potential to utilize environmentally friendly energy sources, proving that sustainability can also be aesthetically pleasing.

History of the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower was opened to the public on March 31, 1889, after 2 years and 2 months of construction, becoming the tallest building in the world and gaining international fame. It was the main monument of the 1889 Paris World’s Fair, which marked the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, aiming to showcase the boldness of the French in industry and technology to the world. The design of the Eiffel Tower began with two engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, who worked at the Eiffel Institutions Company. Initially skeptical, Gustave Eiffel purchased their patent rights and announced his own plan in 1885. On July 8, 1887, Eiffel and the government signed a contract stating that starting from January 1, 1890, Gustave Eiffel would have the commercial rights to the tower for 20 years, after which ownership would transfer to the city of Paris. However, many people questioned the tower’s aesthetics and usefulness, and even residents of the Champ de Mars area protested against building such a large monument. Despite this opposition, the Eiffel Tower survived demolition due to its unique structure, height, and growing public interest, eventually becoming a symbol of Paris and France. As a result, the Eiffel Tower held the record as the tallest building in the world for 40 years until the Empire State Building was built in New York in 1931. Today, travelers from all over the world visit France to see the Eiffel Tower.

Materials of the Eiffel Tower – Characteristics of Steel

The wrought iron used to build the Eiffel Tower underwent a refining process called puddling, which removes excess carbon when the ore is melted. This process produces pure iron. However, to protect the iron from corrosion, it must be coated with thick paint every seven years, a practice that continues to this day. The iron plates and beams produced through the puddling process were pre-assembled using rivets at the Eiffel factory in Levallois-Perret. They were then transported to the Eiffel Tower construction site for assembly. Thanks to this prefab system, the Eiffel Tower was built in a record time of 2 years, 2 months, and 5 days.

Iron and steel account for 8% of the world’s final energy consumption and 7% of energy-related CO2 emissions. In infrastructure such as construction and transportation, wrought iron and steel are essential materials. More than half of the world’s steel is used in buildings and infrastructure. Steel is the second most used material in buildings. Although the Eiffel Tower is made of wrought iron, to reduce urban carbon emissions, it is important to avoid the use of steel when constructing buildings and to shift to verified low-carbon alternatives. There are two main ways to reduce carbon emissions in the steel sector: 1) using carbon-based methods combined with carbon capture technology, and 2) replacing carbon (coke) by chemically converting iron ore into pig iron using alternative reductants such as hydrogen or direct electrolysis (Rissman 2020). Producing iron from scrap in electric arc furnaces uses 60-80% less energy compared to traditional iron production.

The process of the Eiffel Tower becoming eco-friendly

The Eiffel Tower consumes as much energy as a city with a population of 3,000 people, mainly due to the elevators used by visitors for about 15 hours a day, 365 days a year. To achieve Paris’s goal of reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions by 25% by 2020, the Eiffel Tower underwent renovations over four years. The renovation project, costing 28 million pounds, was completed in 2015.

Two wind turbines have been installed inside the Eiffel Tower, positioned approximately 400 feet above ground level. On the second floor of the Eiffel Tower, a 21-foot-tall turbine has been strategically placed at a location with optimal wind exposure and painted the same color as the tower to blend in aesthetically. The turbine manufacturer, UGE International, preserved the tower’s aesthetic and structural integrity by avoiding the use of large lifting equipment. Instead, skilled workers used ropes, winches, and pulleys to manually hoist the turbine components into place. Additionally, rather than relying on concrete or traditional support structures, a steel foundation was constructed beneath the turbines to absorb vibrations and withstand resonant frequencies. Although there were initial concerns about noise from the turbines disturbing the restaurant directly below, the turbines operate quietly at under 40 decibels and are discreetly painted to avoid visual disruption. The two turbines generate a combined 10,000 kWh of electricity, which is used to power the first-floor restaurant, gift shop, and exhibition spaces. While this represents only a small portion of the Eiffel Tower’s annual energy consumption of 6.7 GWh, the presence of renewable energy within such a globally recognized landmark serves to inspire positive public perception and awareness of sustainable energy solutions.

In addition to the installation of wind turbines, the Eiffel Tower has also undergone renovations and incorporated solar panels. A 107-square-foot area of solar panels installed on the Ferrie Pavilion generates enough energy to provide approximately half of the hot water needed for the two pavilions.

The rainwater collection system channels rainwater to the restrooms, helping to reduce water usage. On the first floor, window placements were adjusted to avoid obstructing the view while reducing floor heat by 25% during the summer, thereby saving on cooling costs. The lighting on the first floor was replaced with LED lights, which are significantly more energy-efficient than the previous fixtures. These energy-saving measures across various parts of the tower have led to a 30% reduction in the tower’s overall energy consumption.

Challenges Faced by the Eiffel Tower: Maintenance

Since 1892, the Eiffel Tower has been completely repainted approximately every seven years, following the recommendation of Gustave Eiffel. Painters use the traditional method of hand-painting, the same technique that was employed during Eiffel’s time. In preparation for the 2024 Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Eiffel Tower is undergoing its 20th repainting. Structures like the Eiffel Tower require repainting every 5 to 10 years, which incurs significant economic costs and increases carbon emissions. The labor costs associated with repairs and the economic impact caused by delays in scheduled services due to maintenance can be substantial. As buildings grow larger, these impacts become even more pronounced.

4. The Importance of Sustainable Cities and Landmarks

France’s Carbon Neutrality and Urban Landmarks

France has one of the lowest per capita carbon emissions among developed countries, largely due to its electricity production being dominated by nuclear energy (71%) and hydropower (10%). However, the aging of nuclear power plants and continued reliance on fossil fuels in the transportation sector have led to a rise in overall CO₂ emissions. In 2019, the Energy and Climate Law legally enshrined France’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, strengthening its emissions reduction pathway (an 85% reduction compared to 1990 levels by 2050). Despite these efforts, France did not meet its 2015 Paris Agreement targets for energy efficiency, renewable energy deployment, or carbon reduction in 2021. According to the IEA’s 2021 France report, timely decisions on the future energy mix and accelerated investment in clean energy transitions are essential for France to meet its 2030 climate and energy goals. Just as France must implement sustainable and just energy transition policies within the next decade, South Korea also needs to reassess its plans and enhance its efforts to reduce carbon emissions. To raise public awareness of carbon neutrality and the importance of renewable energy, it is effective to leverage urban landmarks and tourist attractions to foster positive public perceptions.

The Eiffel Tower in Paris, one of the most visited landmarks in the world, delivers a message of sustainability to people around the globe. Today, the Eiffel Tower goes beyond serving merely as an aesthetic landmark—it now produces energy through the use of renewable sources.

Special Events at the Eiffel Tower, “Paris de l’hydrogène”

To illuminate landmark structures, lighting inside the tower or external generators are usually required. Recently, however, there was an event called “Paris de l’hydrogène” where the Eiffel Tower was lit using renewable hydrogen energy. Typically, diesel engine generators are used to power the lighting for Eiffel Tower events. But this generator, equipped with a hydrogen fuel cell system, produces only water and heat by reacting hydrogen with oxygen, and operates silently. This special event demonstrated that power can be supplied to fuel cells using hydrogen—a clean fuel that emits no carbon dioxide—and conveyed a hopeful message to countless tourists about the possibility of sustainable development. It also symbolizes that clean energy technologies could be applied to other landmarks and monuments beyond France in the future.

Korea’s Landmarks and Carbon Neutrality

France is advancing projects for a sustainable tourism transition through collaboration among government ministries such as the Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Economy, and Ministry of Tourism. Recently, due to the rising popularity of K-culture, many tourists are flocking to Korea, and the government must also prepare to shift toward responsible tourism in line with global trends. Similarly to the Eiffel Tower case in Paris, Korea can showcase a vision for sustainable cities through eco-friendly renovations of landmarks, the application of renewable energy, and green urban planning. In particular, energy savings and renewable energy implementation in existing buildings like Seoul’s landmarks—Namsan Tower and Lotte Tower—along with making cities more environmentally friendly, are essential steps to achieving net zero by 2050. If many cities make their popular tourist destinations sustainable, more countries will be encouraged to green their urban areas, increasing the likelihood of achieving net zero worldwide.

References

- Paris 2024 Official Website: Having the carbon footprint of the games

- Paris Tourist Office Official Website: Paris a sustainable city

- Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau

- UNEP & Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture (2023.09.) Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future

- UNFCCC Official Website: The Paris Agreement

- UNFCCC Official Website: City of Paris Carbon Neutral by 2050 for a Fair, Inclusive and Resilient Transition https://unfccc.int/climate-action/un-global- climate-action-awards/climate-leaders/city-of-paris

- Un Jour de Plus à Paris Official Website: The History of the (tumultuous) construction of the Eiffel Tower

- 한국관광 데이터랩 (2022.05.25.) 지속가능한 관광지 조성을 위한 프랑스 관광업계의 변화

- ASME Official Website (2015.08.05.) The Eiffel Tower Goes Green – EcoFriend (2019.06.19.) Here’s how Eiffel Tower is going green

- Energy Observer (2021.06.03.) Lighting up the Eiffel Tower with green hydrogen: we made it!

- Explore France (2023.07.25.) Paris 2024 in figures: record-breaking games

- Forbes (2022.11.23.) A Guide To The Paris Agreement And Intl. Climate Negotiations (Part 1)

- Galvanizers Association (2021.07.16.) Reducing Whole Life Carbon Footprint by Avoiding Maintenance and why carbon footprint should be a whole life calculation

- IEA (2021.11.) France 2021 Energy Policy Review

- IOC Official Website (2023.07.31.) Media > Opinion > Paris 2024: raising the bar for more sustainable sporting events

- National Geographic (2018.05.30.) From Historic to Cutting Edge: Revitalising Iconic Buildings

- Timeout (2021.11.03.) How Paris plans to become Europe’s greenest city by 2030

- The Eiffel Tower Official Website (2020.03.04.) 15 essential things to know about the Eiffel Tower

- The Eiffel Tower Official Website (2022.12.20.) Major work to maintain the Tower for the future

Suggested Reading: Top 10 Global Carbon-Neutral Travel Spots – Discover the ‘Green Hot Spots’!

- No Earth, No Tennis: The Championships, Wimbledon

- An Eco-Friendly Football Stadium that impresses the World: Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

- An Avenue of Art that Dreams of Tomorrow: Broadway

- Sustainable World Tours, New Paradigm in the Cultural Industry: Coldplay’s World Tour

- A Green Theme Park, Walt Disney World: Magic Kingdom in Florida

- Making History as the World’s First and Best in Sustainability: The Natural History Museum, UK

- Italy’s Efforts to Rescue Venice from Submersion: A Model City for Climate Adaptation Tourism

- A Tower Shaping a Sustainable Future for the Community by Practicing ESG Values: Tokyo Skytree

- Leading the Green Transition of Australia’s Cultural and Arts Scene: Sydney Opera House