1. An Event Only Humans Enjoy?

A Sports Event the Whole World Awaits — But What About Nature?

The World Cup, the Olympics, and the Asian Games — without a doubt, these major sporting events are what bring the entire world together in excitement and anticipation. There are few events that make our hearts race in unison with a mix of hope and tension, the way sports do. While travel, concerts, and exhibitions certainly add joy to our everyday lives, it’s the grand international sporting events that truly capture global attention. From the Olympics to the World Cup and Major League Baseball, people can enjoy these events from the comfort of their homes via TV broadcasts, or join crowds watching on giant screens to cheer together. However, for die-hard sports fans who want to feel the heat of the match and experience the energy of the moment firsthand, nothing beats being right there in the stadium.

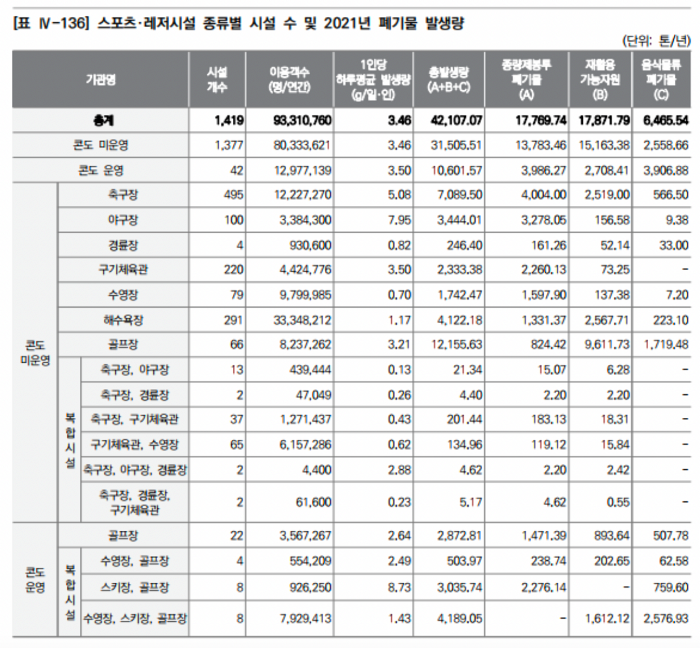

With hearts full of excitement, spectators enter the stadium ready to pour out their passion — and perhaps some of their daily stress — into cheering for their favorite teams. By the time the match ends, they often leave the venue exhausted but emotionally refreshed. But is the relief truly complete? According to the 6th National Waste Statistics Survey Report published by South Korea’s Ministry of Environment in 2022, the amount of waste generated annually at sports and leisure facilities in 2021 was staggering: 7,089.5 tons at football stadiums, 3,444.01 tons at baseball stadiums, 2,333.38 tons at indoor gymnasiums, and a whopping 12,155.63 tons at golf courses. These figures show a significant increase compared to the 5th National Waste Statistics Report from 2017. Back then, football stadiums generated only 1,342 tons of waste per year and baseball stadiums 2,203 tons — meaning waste at football venues alone rose by more than 5,700 tons in just five years. All this occurred despite escalating climate crises and the global COVID-19 pandemic — a stark reminder of the consequences of human interference with nature. Even as awareness grew, waste generation at sports and leisure facilities has only increased.

This reveals an uncomfortable truth: what we release during a game isn’t just built-up stress. Sporting events are not only arenas of passionate cheering — they are also spaces where we discharge both our conscience and our waste. People don’t just enjoy the game itself. These events offer the convenience of consuming and discarding large amounts of food and drink, often packaged in disposable containers, with little thought for the environmental impact.

The debt that sports owe to nature goes far beyond the waste generated during matches. Major sporting events like the World Cup, the Olympics, the Asian Games, and Major League Baseball produce significant carbon emissions across multiple areas — from athletes traveling by air, to the energy required for broadcasting, to the ongoing operation and maintenance of teams and facilities.

Let’s take football, one of the most representative sports, as an example. According to a study by Selectra, a European energy company, sports account for about 0.3% to 0.4% of the world’s total carbon emissions. While 0.3% to 0.4% may seem like a small figure, it is roughly equivalent to the total carbon emissions of Denmark. In other words, just a few sports events held over a short season can emit as much carbon as an entire country does in a year. Moreover, The Athletic, a specialized sports news outlet, highlighted that Manchester United alone emitted 1,800 tons of carbon dioxide during their preseason travels between Thailand and Australia. This amount is comparable to the carbon dioxide produced by 350 households using electricity for an entire year.

arge-scale sports events are not exempt from these issues. Recognizing the seriousness of the problem, the sports world has declared commitments to carbon neutrality, promoting concepts like the Carbon Zero World Cup and the Green Olympics. In South Korea, the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics represented such an effort, and more recently, the Qatar World Cup drew widespread attention. Both events boldly declared their ambitions to achieve carbon neutrality and proudly branded themselves as ‘eco-friendly sports events.’ However, these claims ultimately turned out to be little more than empty promises. The PyeongChang Olympics faced criticism for contradictory actions such as deforestation undertaken specifically for the event, despite its eco-friendly claims. Similarly, the Qatar World Cup was widely criticized by various media outlets for distorted methods of measuring carbon emissions and unreasonable investments in newly constructed stadiums. Both events ended up with the ignominious label of greenwashing rather than genuine sustainability.

Carbon Neutrality in Words Only, Climate Villain in Reality: The Qatar World Cup

A clear example of a carbon-neutral sports event that ended up as mere greenwashing is last year’s Qatar World Cup. The tournament featured seven newly built stadiums constructed solely for the event. The construction of these seven stadiums alone generated 654,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions. Moreover, these stadiums inevitably continue to produce additional carbon emissions depending on how they are used post-tournament. The energy required for maintenance and operation is substantial, and if the stadiums are left unused or underutilized, they risk becoming extravagant, wasteful monuments built just for show. Despite constructing seven large, lavish stadiums that are difficult to sustain for continuous use after a single World Cup, FIFA promoted the Qatar World Cup on its website as an eco-friendly event achieving carbon neutrality. One flagship example of their green efforts was the Abu Dhabi Stadium, also known as the “974 Stadium”. The nickname “974” comes from the fact that the stadium was made by recycling 974 shipping containers. Since the containers are made of steel and planned to be fully dismantled and reused after the tournament, FIFA claimed this design reduced carbon emissions and exemplified environmentally friendly stadium construction. Following the conclusion of the Qatar World Cup, all the containers that made up the 974 Stadium were indeed dismantled as planned.

However, there is a hidden trap here. Since the stadium was built by recycling shipping containers and is planned to be dismantled and recycled again, the word “recycling” naturally evokes an eco-friendly image. But whether it is truly environmentally friendly requires closer examination. As mentioned earlier, the construction of the stadiums for the Qatar World Cup alone emitted 654,000 tons of carbon dioxide. Remarkably, just building the so-called “974 Stadium” — one of FIFA’s main claims to environmental friendliness — generated 438,000 tons of CO₂. Including emissions from stadium construction, the total carbon footprint of the Qatar World Cup reached 3.6 million tons, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of about 460,000 households. This amount was released over the course of only a few days of competition, matching the yearly carbon footprint of hundreds of thousands of homes. Qatar is not the only culprit behind such massive carbon emissions. The 2018 Russia World Cup emitted around 2 million tons of CO₂, and the 2016 Brazil World Cup emitted 4.5 million tons. At this point, it’s clear that large-scale sports events have become major contributors to global warming in the era of climate crisis.

2. Wimbledon Sheds Its Image as a Climate Villain

A New Direction in the World of Sports

While the ball bounces back and forth across the court, capturing the joys and sorrows of millions around the world, the Earth silently bears the heavy burden of carbon emissions. Amid the thunderous cheers and applause of spectators worldwide, pollutants have been released in concentrated bursts. Sports events have long been celebrated on a grand scale, but only by imposing a significant burden on the planet. However, the waste left behind after every game and event, along with the massive carbon emissions generated by frequent air travel, can no longer be ignored. Carbon neutrality has become an urgent, unavoidable challenge for the global community — with no exceptions. Because this issue concerns every living being and ecosystem on Earth, no sector can escape the climate crisis unless it reduces carbon emissions and ultimately achieves net-zero. The sports industry, too, must share this responsibility.

However, many tournaments that have been promoted as eco-friendly and carbon neutral have ultimately turned out to be nothing more than greenwashing when examined closely. Angry baseball fans have even protested, holding signs that read “No Earth, No Baseball,” expressing their frustration over the unfulfilled promises of “green sports.” Yet, despite demands from citizens and criticism from environmental groups, significant changes in the sports world still seem lacking. What tends to receive the most attention in sports events are the athletes’ wins and losses, and the grandeur of opening and closing ceremonies. Meanwhile, humanity continues to lose the battle against the climate crisis. So, is there really no alternative? Must sports continue to be the enemy of nature?

Sports Events in Harmony with Nature

There is a sports event that clearly answers “No” to that question. It proves that even massive sporting events, eagerly anticipated by countless spectators, can be environmentally friendly. A prime example of this is the Wimbledon Championships. Even those who are not particularly interested in sports have likely heard of the Wimbledon Championships. Established in 1877 in the UK, it is the oldest tennis tournament in the world, boasting a long history, a distinguished reputation, and high prestige. Today, the tournament is held at the All England Lawn Tennis Club in Merton, London. Besides the main Center Court, several grass courts are arranged around the venue, allowing multiple matches to take place simultaneously.

The Wimbledon Championships are the third of the four Grand Slam tournaments held annually, following the Australian Open and the French Open. Typically, Wimbledon takes place from late June to early July and runs for about two weeks. So, how do Wimbledon’s efforts to reduce environmental impact truly differ from the “greenwashing” seen in other sporting events? Is the so-called “sustainability” claim by Wimbledon just another example of greenwashing designed to paint their actions in a positive light? We have already seen countless cases where companies and organizations distort or exaggerate information while claiming sustainability. Naturally, it is reasonable to suspect that Wimbledon’s efforts might also be nothing more than eco-friendly posturing. However, Wimbledon may be taking a somewhat different path than the rest of the sports world. While their efforts may not be perfect, it cannot be said that their push for carbon neutrality is meaningless. At the very least, it is clear that they are striving for meaningful change.

Carbon Emissions Reduced to 1/100 — Wimbledon Makes It Happen

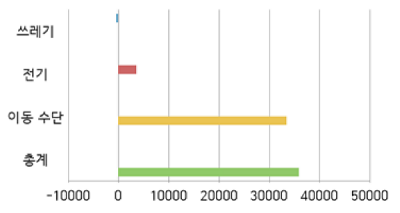

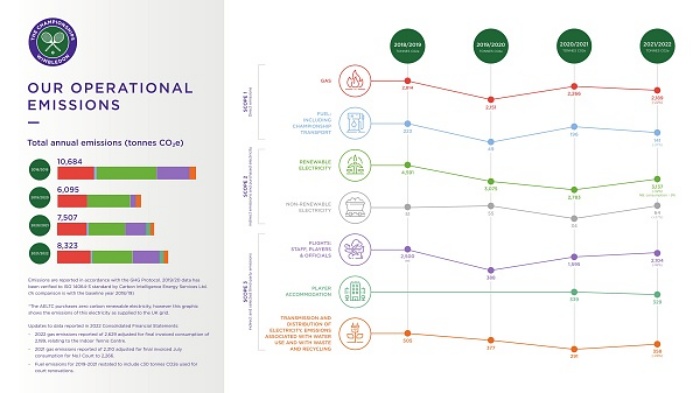

There is a clear result that shows Wimbledon’s carbon neutrality and sustainability efforts are far from mere empty boasts. That is the amount of carbon emissions produced by the Wimbledon Championships. The total carbon emissions from the tournament amount to 35,894 tons. At first glance, this might still seem like a considerable amount. However, compared to the World Cup figures mentioned earlier, it is only about one one-hundredth of that amount — a testament to how much effort Wimbledon has put into reducing its carbon footprint. How was such an impressive result achieved?

Let’s analyze the carbon emissions of the Wimbledon Championships. Out of the total 35,894 tons of carbon emitted, the largest share comes from transportation. Carbon dioxide emissions from transportation accounted for 33,461 tons, representing 91.3% of the total.

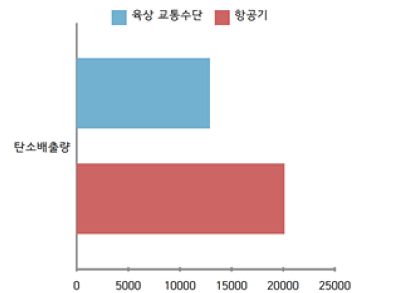

The chart above, provided by The Eco Experts, visualizes the carbon emissions from various modes of transportation used during the Wimbledon Championships. The largest contributor by far was airplanes, which emitted about 20,000 tons of carbon dioxide. Air travel is the highest source of CO2 emissions not only at Wimbledon but also at other sports events. The travel of players and spectators by plane accounts for more than half of the total carbon emissions generated by sports competitions. Reducing carbon emissions from air travel remains a persistent challenge for sports events, including Wimbledon, and is a critical issue to address moving forward. However, compared to the approximately 1.8 million tons of carbon emissions from flights during the Qatar World Cup, Wimbledon’s 20,000 tons represent only about 1/90th of that amount, making it a relatively small figure. This is partly because only 11% of the 500,000 spectators attending Wimbledon traveled by plane.

For ground transportation, Wimbledon provided electric vehicles directly. During the tournament, Wimbledon offered 20 electric cars for players to use for transportation, and spectators were able to move around using electric buggies. These measures by Wimbledon demonstrate their efforts to reduce carbon emissions generated during transportation.

Wimbledon’s Zero-Waste Field

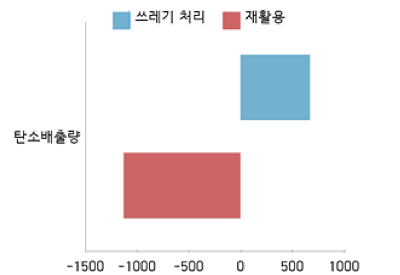

We can’t ignore the amount of carbon dioxide produced in other areas as well. In particular, the figure of –457 caught my attention, making me wonder if I was seeing it wrong. In terms of waste generated at sports events, a negative number is practically impossible. There are countless reports of stadiums struggling under the weight of trash left behind by spectators. This issue isn’t unique to stadiums in Korea; Liverpool in the UK faces the same problem. So how is it possible that at the Wimbledon Championships, also held in the UK, the total carbon dioxide emissions from waste are negative? How could this be?

The Wimbledon Championship adopted a strategy of offsetting carbon emissions by recycling waste. The amount of carbon emissions reduced by recycling waste exceeded the emissions generated from processing the waste produced within the Wimbledon venue. Thanks to this, Wimbledon was able to achieve negative carbon emissions in the waste management category. In Korea, people typically eat chicken and beer when watching games, whereas in the UK, it is traditional to enjoy strawberries with cream or fish and chips while watching tennis matches. Of course, at the Wimbledon Championship, food waste such as leftover strawberries, cream, and fish and chips was generated. However, instead of sending this food waste to disposal sites, Wimbledon composted it for use in agriculture. When properly fermented, food waste can become excellent compost for organic farming.

The Wimbledon Championship declared its goal to create a zero-waste venue. During the tournament, the total amount of waste generated in connection with the event was approximately 5,600 tons. Of this, about 10% was incinerated, while an estimated 90% was recycled. To realize the zero-waste stadium policy, Wimbledon completely banned the use of plastic straws and used only reusable cups for coffee and other beverages served at the venue.

The Wimbledon Championship not only avoids using disposable coffee cups but also installed numerous water fountains throughout the venue so that spectators don’t have to buy bottled water. Spectators were encouraged in advance to bring their own tumblers, allowing them to refill for free at these water stations. But that’s not all. One of the highlights of any sports event is the limited-edition merchandise (MD goods). It’s common to see fans lining up early in the morning at sales booths to buy these items. However, these numerous products inevitably come with the inconvenient baggage of packaging waste. Through merchandise sales, fans enjoy collecting meaningful items and the event organizers generate profit. But what we also get, unfortunately, is not just that. We also end up with carbon emissions generated from the production and distribution of these goods, as well as from processing the packaging materials surrounding them.

Wimbledon has reduced unnecessary carbon emissions from merchandise sales by switching all product packaging to recyclable materials and completely eliminating the use of plastic packaging. For example, one of the products, the Wimbledon towel, is packaged with a card band that bears the FSC certification mark.

FSC certification stands for Forest Stewardship Council. It refers to a system established by an international NGO called the Forest Stewardship Council, which aims to protect forest resources and promote sustainable forest management. The certification involves evaluation by a third-party organization based on principles and criteria considering environmental, social, and economic impacts. Products made from wood sourced from FSC-certified forests that comply with FSC’s environmental and social standards, or products made from recycled materials after consumption or recycled materials before consumption, can receive the FSC certification mark through this assessment.

Energy Innovation Toward Carbon Neutrality

At Wimbledon, the carbon emissions generated during each match are calculated and published in a report on the official website. According to this report, the use of renewable energy sources far exceeds that of non-renewable sources. The carbon emissions resulting from the use of non-renewable energy—namely fossil fuels—amounted to just 64 tons in 2022. While this figure represents nearly double the usage compared to the previous season in 2021, making it subject to criticism, Wimbledon is making continuous efforts to reduce this number to zero.

Since 2019, Wimbledon has taken steps toward achieving net zero (carbon neutrality) by adopting renewable energy sources. Starting with the 2022 tournament, solar panels have been installed on the roof of the main stadium to help generate electricity. Additionally, since 2019, Wimbledon has been purchasing and using renewable energy. All lighting around the Wimbledon grounds now uses high-efficiency LED lamps, minimizing carbon emissions associated with lighting.

However, fossil fuels and natural gas have not yet been completely eliminated. As of the 2022 season, carbon emissions from natural gas use amounted to 2,189 tons. Wimbledon has announced its plan to completely phase out the use of fossil fuels and natural gas by 2030, replacing them entirely with renewable energy sources.

Eco-Friendly Uniforms Are the New Trend

Uniforms are also an essential part of any sporting event. At Wimbledon, players traditionally wear all-white outfits, while ball boys/girls and officials wear uniforms in navy and white designs. This tradition has remained virtually unchanged since the tournament’s inception, and the Wimbledon uniform has become a symbol as enduring as the tournament itself. However, recently even this long-standing tradition has seen a shift. The uniforms worn by staff such as referees and ball kids during matches are now eco-friendly. Wimbledon has shown its commitment to sustainability by paying attention to every detail — even the uniforms worn during the tournament.

The new uniforms for Wimbledon were released by the brand Polo Ralph Lauren, which has been in charge of Wimbledon’s uniform design for 17 years. In line with Wimbledon Championship’s efforts to become an eco-friendly sporting event, the brand recently introduced eco uniforms. These uniforms are made from sustainable and environmentally friendly materials. All the uniforms worn by court staff, including chair umpires and line judges, are made entirely from recycled materials. Polo Ralph Lauren stated that the uniforms were designed to align with Wimbledon’s vision—maintaining the necessary functionality for tennis while focusing on sustainability.

Strawberries instead of chicken!

Earlier, the tradition of eating strawberries while watching matches at the Wimbledon Championships was briefly mentioned. Although it was a light and passing remark, the question of what we eat actually has a significant impact on environmental conservation. At first glance, one might think, “Is eating strawberries really that important?” However, such seemingly trivial dietary habits and choices of ingredients are major unseen contributors to carbon emissions. The issue of what we eat is a critical matter that can either drive the Earth into danger or help save it. Recently, due to growing awareness of these issues, the demand for veganism has been steadily increasing.

First of all, the food provided at Wimbledon is locally sourced and produced in season. Local food is an excellent choice because it minimizes food mileage—the carbon emissions generated during the transportation process from the place of production to the consumer’s table. Globally, greenhouse gases emitted during food transportation account for about 6% of total carbon emissions worldwide. Additionally, 20% of carbon emissions related to food come from the transportation process alone. Moreover, producing crops in season means they are grown in a way that respects natural systems, rather than relying on greenhouse farming. In fact, growing out-of-season produce requires maintaining greenhouse temperatures, which consumes a large amount of fossil fuel energy and increases greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, the carbon footprint of eating vegetables that are not in season is inevitably higher. Wimbledon has taken these factors into account and has found the best possible way to ensure that even the food eaten by spectators does not accelerate the climate crisis.

Furthermore, strawberries are a completely vegan food. The carbon footprint of plant-based foods such as fruits and vegetables is significantly lower compared to meat. In Korea, when watching sports games, people usually gather at barbecue or chicken restaurants to eat and drink while watching the broadcast on a big screen, or they order chicken delivery to watch the game on TV at home. However, sports events combined with meat consumption are a shortcut to depleting and exhausting the Earth faster for the sake of human enjoyment. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, livestock farming accounts for 15% of total greenhouse gas emissions, which is even higher than the 13.5% emitted by all the cars worldwide.

The water footprint of meat has been revealed as 8,763 liters per 1 kg of beef, 5,988 liters per 1 kg of pork, and 4,325 liters per 1 kg of chicken. Additionally, producing 200 grams of beef requires 1.6 kg of grain, while producing 1 kg of chicken requires 1.5 kg of grain. At first glance, 1 kg of chicken and 1.5 kg of grain don’t seem very different in quantity. But consider this: an average chicken weighs about 1 kg, and a typical bowl of cooked rice contains about 100 grams of uncooked rice. This means that eating one chicken wastes the equivalent of 15 servings of grain. If we switch to one vegetarian meal a day, we can reduce about 3.25 kg of carbon emissions daily. In Korea, instead of enjoying chicken and beer while watching games, if people accompanied their snacks with fully vegan options like fruits—following Wimbledon’s tradition—it would be possible to reduce daily CO₂ emissions by up to 4.27 kg.

The Earth’s Heritage: Biodiversity

Wimbledon also spares no effort in conserving biodiversity. To protect local biodiversity, all the ingredients used at Wimbledon come from native seeds. Preserving biodiversity and maintaining a variety of species of plants and animals is extremely important. When monoculture farming is practiced using seeds distributed by large corporations, specific soil nutrients are depleted, the nutritional balance of the soil necessary for plant growth is disrupted, and the variety of microorganisms becomes homogenized. This ultimately leads to soil erosion and degradation. If farming continues in this way, soil loss occurs in the cultivated land, and due to damage to the topsoil, agriculture can no longer be sustained on that land. Moreover, plants become more susceptible to diseases. When an infectious disease spreads among plants, fields growing only a single variety can be entirely wiped out, whereas fields with multiple varieties may have some plants with genes resistant to the disease that survive. The Irish Potato Famine was also a tragic consequence of planting only one variety nationwide—chosen for taste and productivity—rather than efforts to preserve biodiversity.

Native seeds are species that have originally grown in that land. Therefore, they are the plants best suited to the soil composition and climate of that area. Preserving native seeds helps restore ecosystems that are being disrupted by the increasingly uniform plants on our dining tables. It is also an effort to secure food security in preparation for the climate crisis.

At Wimbledon, to protect biodiversity, plants are donated to local communities, and the walls between tennis courts are planted with flowers and grasses to create natural, eco-friendly partitions that provide habitats for various insects and birds. Additionally, to preserve the native oak trees living in Wimbledon Park, acorns are harvested and replanted, among other activities aimed at enhancing local biodiversity.

3. Enjoying pleasures within the Earth’s limits

The Future of Sports: What Wimbledon Suggests

Through the example of Wimbledon, we have seen that large-scale sports events held once a year or every few years can certainly be enjoyed without harming nature. As the Wimbledon Championships demonstrate, if sports events adopt slightly different approaches and embrace a mindset of caring for the environment, they can become a solution to the climate crisis rather than a cause of it. We can learn a great deal from Wimbledon’s pioneering example of forging a path for sports to coexist harmoniously with nature. Wimbledon has proven that it is entirely possible to find ways to host sports events while living in harmony with the environment.

In fact, besides the Wimbledon Championships, the US Open, another major tennis tournament, is also making significant efforts to minimize the environmental impact of sports events on the climate crisis. Since 2008, the US Open has implemented a sustainability program and has continued to expand and enhance various initiatives within the program. For example, 24% of the food offered is vegetarian, and 8% is vegan. Approximately 70 tons of food waste generated are composted or recycled into renewable energy sources. High-efficiency LED lighting has been installed around the courts to maximize energy efficiency, and 95% of the waste produced during the tournament is recycled. The largest source of carbon emissions, transportation, has been addressed by encouraging the use of subways and public transit instead of airplanes, significantly reducing carbon emissions. In this way, many major sports events are proactively exploring ways to enjoy their activities in harmony with the Earth.

Shall we give it a try too?

South Korea is already counted among the countries notorious as climate villains. Reckless consumption, mass production, and mass disposal dominate. Perhaps scarred by the material scarcity during times of war, many rush like a swarm to discard what they have and buy new things just because they are newer, bigger, faster, or better. The hardship of the past “barley hump” is now sought to be eased with pork belly and fried chicken. Unlike in the past when many did not even know where Korea was, nowadays, intoxicated by the “Korean Wave,” people focus only on the booming sounds of K-pop filling concert halls and fail to see the trash-strewn venues. Ultimately, just as Korea seems to be overcoming its past trauma, it simultaneously becomes a climate villain. It would be nice if the carbon dioxide emitted in Korea stayed only in its skies, but that is not the reality. In countries like Korea, where consumer culture is well-developed and living standards are relatively high, the carbon dioxide emitted returns in the form of disasters—floods, droughts, hunger, and poverty—to the poorest regions of underdeveloped or Third World countries. In the end, the myth of progress we raised amidst clouds of dust has pushed the poor into floods, famine, hunger, and poverty.

In such a situation, what can we do? Should we feel guilty simply for hosting large-scale sports events to raise Korea’s standing? At least Wimbledon says no. However, as the Wimbledon Championships have shown, it is necessary for everyone to join forces and make collective efforts.

First, in Korea, stadium lighting could be replaced with high-efficiency LED lights. On game days, sports stadiums are often extremely bright, with dazzling lights causing significant light pollution. Using LED lamps that reduce light pollution while consuming less electricity would help minimize environmental damage. Additionally, stadiums in Korea don’t just host baseball or soccer games; e-sports events such as the League of Legends World Championship, commonly known as the “Worlds,” as well as K-pop idol concerts, are also held. A common feature at these events is the sale of merchandise (MD products). Currently, many of these merchandise items are packaged in single-use plastics or vinyl. However, if, like Wimbledon, they were packaged using recyclable, eco-friendly paper, it could significantly reduce non-recyclable waste and single-use packaging waste.

References

- 환경부 (2022) 전국폐기물통계조사 : 제6차(2021~2022년)

- Forest Stewardship Council Korea Official Website: FSC 로고를 사용하는 방법

- The Championship Wimbledon Official Website: Sustainability

- The Championship Wimbledon Official Website: What does Net Zero mean for the AELTC?

- The US Open Official Website: Green Initiatives

- Zero Carbon Academy (2023.07.03.) Game, set and match? Wimbledon aims to reduce its impact as tennis grapples with sustainability challenges

- The Eco Experts Blog (2022.09.30.) What is Wimbledon’s Carbon Footprint?

- 그린포스트코리아 (2020.12.25.) 크리스마스에 넷플릭스 보면서 치맥 먹는 게 환경오염의 원인?

- 비건뉴스 (2023.03.07.) [에코&비건] 채식이 지속가능한 이유

- 환경일보 (2018.02.21.) 평창올림픽의 그늘 ‘가리왕산 스키장’ 복구 힘들어

- 한국일보 (2022.11.23.) 카타르월드컵이 친환경적이라고?… 사실은 ‘그린 워싱’이다

- ESG경제 (2022.07.06.) 식품 운송할 때 탄소 배출, 세계 탄소배출량의 6% 차지

- Euronews (2021.10.28.) Climate crisis: How can football make a difference?

- KBS뉴스 (2013.05.17.) [이슈&뉴스] 넘치는 쓰레기, 몸살 앓는 경기장

- The Athletic (2022.08.01.) Floods, fires and why football can play a big role in tackling climate change

Suggested Reading: Top 10 Global Carbon-Neutral Travel Spots – Discover the ‘Green Hot Spots’!

- An Eco-Friendly Football Stadium that impresses the World: Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

- An Avenue of Art that Dreams of Tomorrow: Broadway

- Sustainable World Tours, New Paradigm in the Cultural Industry: Coldplay’s World Tour

- A Green Theme Park, Walt Disney World: Magic Kingdom in Florida

- Making History as the World’s First and Best in Sustainability: The Natural History Museum, UK

- Italy’s Efforts to Rescue Venice from Submersion: A Model City for Climate Adaptation Tourism

- A Tower Shaping a Sustainable Future for the Community by Practicing ESG Values: Tokyo Skytree

- Leading the Green Transition of Australia’s Cultural and Arts Scene: Sydney Opera House

- Sustainable Olympics and the Eiffel Tower: The 2024 Paris Olympics and the Eiffel Tower